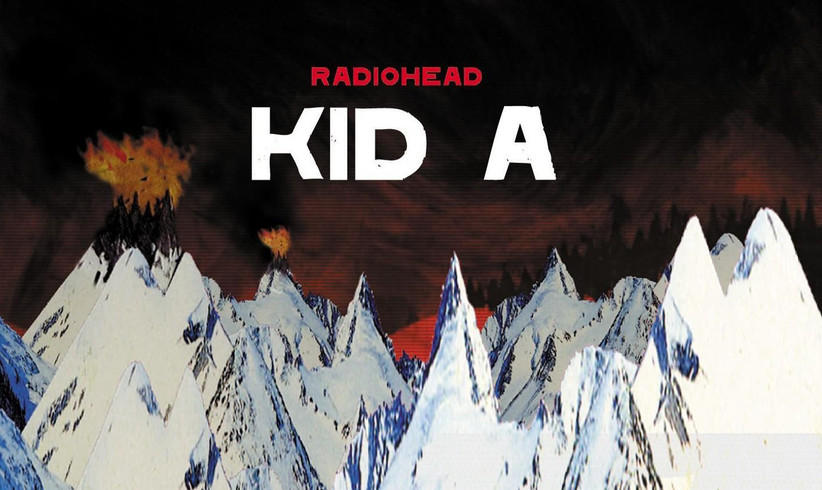

How Radiohead broke their own mold with ‘Kid A’ to create the ultimate existential soundtrack.

On its 20th birthday, Kid A still sounds as remarkable as ever, and its release marked a sea change for its creators.

By the end of the nineties, Radiohead were the darlings of the alternative music world. Hidden behind the melancholic enigma of Thom Yorke’s words, they’d built a loyal fanbase of equally world-dreading folk and were soundtracking their lives. In 2000, however, the band would leave behind a huge amount of the form they’d taken on until that date, with the release of Kid A.

An anxious, electronica-meets-dystopia world, cut off sonically from almost anything else around at the time, haunting yet so completely engrossing. Every listen leaves an indelible mark, and its ambiguous, opaque approach allows your mind to fill in whatever scenery you feel appropriate into its downfall-driven sound. Its a record that maims you emotionally, yet is also so inspired, capturing the 21st century’s ever-growing disconnection between society, politics and reality. It’s no surprise then that, having immersed myself in it once again to write this, its relevance in 2020 feels stronger than ever.

Let’s wind back two decades to the time of its release. Three records in, and by then, their discography had already come to define British music in the nineties. Their debut, Pablo Honey, was a frantic collage that hastily mixed Britpop and Grunge elements with an introverted sensibility. The Bends came next, a forlorn soundtrack to introspective thoughts and unease at the political direction of the time; bounding, striding, lightyears ahead of its alt rock contemporaries. However, it was 1997’s OK Computer, capturing the fear of a world increasingly ruled by technology, its people drowning in disconnection from it, that gave the band legendary status.

“Lacking creativity to keep making more conventional alternative rock, it was time for a sea change.”

Along with various EPs and singles, it seemed that Radiohead had set their mold as a guitar rock band telling the story of a broken society and peeling away its farcical veneer. That style, however, couldn’t stop the real world from catching up with the band, and in the late nineties, they suffered a complete burnout.

Lacking creativity to keep making more conventional alternative rock, it was time for a sea change. Their scope turned to Electronica, which had experienced immense development over the previous decade. Having evolved numerous branches, from the ultra-cool slickness of Massive Attack’s Downtempo to the innovations of IDM from the likes of Aphex Twin, it was ripe to play host to a concept album like Kid A.

Kid A broke almost all form from Radiohead’s previous work. Its sound is synth led, along with endless amounts of looped and warped instrumentation, whilst its lyrical content swaps out intricate detail for a far less revealing approach. Even the album’s release was different, with very little promotional material, no singles to accompany it, and a focus on digital availability, including online streaming.

“It’s more than happy to mumble its words, send you off-piste with odd instrumentation or reverb, and more than anything else, throw endless clues as to what it ‘could‘ be about.”

Most striking of all, however, was its subject. It remains the focus of endless curiosity to this day within Radiohead circles – somewhat familiar to their previous works in expressing dystopian tones, but alien in its delivery. It’s more than happy to mumble its words, send you off-piste with odd instrumentation or reverb, and more than anything else, throw endless clues as to what it ‘could‘ be about.

A concept album about the first human clone?* A wake up call for the 21st century, cynical of capitalism and weary of Westernism? Thom Yorke’s headspace further conceptualised into music – a downward spiral of apathy, reclusiveness and the loss of identity? A motion picture soundtrack, given its gorgeous narrative quality, cross over track transitions, and of course, the name of that final song? Or, as one person reckons, the record that predicted 9/11? Three previous albums with far more definition set you up to expect more of the same on Kid A, but instead you’re left to your own devices. It’s no wonder that the theories about it spiral into wild suggestions.

*The ‘Kid A’ name would surely confirm this, though Yorke said in an interview that its name was “non meaning”. Indeed he said that the human clone theory was his “favourite” of all the album theories.

“It’s no wonder that it still feels so relevant given how well it aligns with today’s interpolation of politics and society, where policy details and the truth seem less important than ever.”

Some of those appear to be towards the ‘clutching at straws’ end, but it’s hard to call them unfounded. The album encourages you to dive into the enigma, and its fully engrossing sound, so completely cut off from any comparable record in Radiohead’s collection or even on a wider extent, heralds it in your mind as something that has to be driven by a profound theory.

For me, it sits somewhere in between a 21st century wake up call and that human clone theory, chronicling the world’s descent into dystopia in reaction to something that would so utterly erode any foundation of humanity. Less than critically dismantling political and economic ideas, it adopts a far more post-modern approach and tackles it from a mental, cultural, experience-driven angle. It’s no wonder that it still feels so relevant given how well it aligns with today’s interpolation of politics and society, where policy details and the truth seem less important than ever. Less than predicting 9/11, is it plausible that Kid A predicted the world of 2020?

It’s this focus on experience, of feeling over detail, that provides the ambiguity to let your mind go wild. ‘The National Anthem‘s menacing bassline conveys fears of political extremism for me, whilst standalone ambient piece ‘Treefingers‘ swirls around you like the paralysing nature of an appalling news story. ‘Idioteque‘, the standout cut of the album’s second half, is like Kraftwerk for the eternally paranoid, a soundtrack to Skynet’s take over.

The endless fear of all manner of subjects that underpins Kid A’s enclosed, electro-ambiguous sound makes it the ultimate existential record. When I first listened to it as a 17 year old, I placed the threat of AI as the album’s antagonist. Today, in lockdown 2020, the seemingly ever-accelerating race to political, environmental or technological doom takes that spot.

“‘Idioteque’, the standout cut of the album’s second half, is like Kraftwerk for the eternally paranoid, a soundtrack to Skynet’s take over.”

Don’t think for a second, however, that that existentialism is an all-negative aspect – this is a record that celebrates its softer moments too. The gentle synths that guide in track 2 (the album’s title namesake) evoking the image of a spaceship quietly coming into land, offer refrain from the terror of facing society – and the rest of the tracklisting for that matter. It’s unsettled for sure, but there is a quaint beauty to it too, as though this the smallest matter might come to bring the end of the world.

And by the end of the album, that’s exactly what it does. ‘Motion Picture Soundtrack’, the ultimate heartbreak finale, is composed of only limited instrumentation, yet has the most human sound of the lot. It’s also the one that hits hardest – Thom Yorke’s always been good at turning the most simple lines into emotion filled wrecking balls but “I think you’re crazy” tops the lot, and at the end of a record as heavy as this, it’s savagely beautiful.

“Kid A’s tone isn’t one that offers hope, its view is that our fate is sealed.”

Kid A was a sea change for Radiohead, ending their era as a guitar rock band and evolving their name into a byline for a modern day equivalent of George Orwell and Philip K Dick set to music. In hindsight, the idea of releasing singles for it makes no sense – none of the tracks feel fully formed without their wider narrative. And that narrative sets whatever story suits you in an existential framing. Radiohead took their dedicated fan base of equally world-dreading people and gave them a playground.

And where an interpretation such as this album predicting the sh*t that would go down in 2020 might seem to have a snarky “I Told You So” quality to it, that’s no so here. Kid A’s tone isn’t one that offers hope, its view is that our fate is sealed. In a time as chaotic as we are in, on an album as ambiguous as this, and for a band who were in such a state as they were at the time, there is an infinite, wonderful comfort in that sense of doom.

‘Kid A’ was released on 2nd October 2000 on Parlophone and Capitol records.

Certification: Personal Favourite.

This is the highest accolade I can award to a piece of music. Nice job Radiohead!

This album is on my Favourite Albums of All Time List.